What We Heard Report: Consulting Canadians on the merits of a Foreign Influence Transparency Registry

November 2023

Executive Summary

In the spring of 2023, Public Safety Canada (PS) held in-person and online consultations on a potential Foreign Influence Transparency Registry (FITR) for Canada. The purpose of the consultations was to solicit feedback from the Canadian public and stakeholders on how Canada might design and implement a FITR to strengthen national security by increasing transparency and general public awareness of foreign influence in Canada.

This What We Heard Report provides an overview of the information received from over 1,000 online respondents and over 80 key stakeholder groups. The report also addresses public commentary in Canadian media on the implementation of FITR.

Overarching Themes

Overall, respondents were in favour of establishing a registry in Canada. They indicated the need for new measures to ensure greater transparency, as well as deter malign foreign influence in Canada. Respondents emphasised the need for clarity: a FITR must appropriately define who must register and what falls within the scope of registrable activities. Respondents also emphasised that a FITR should, to the extent possible, not generate undue administrative burden for registrants. Respondents also supported both financial and criminal penalties, and adequate enforcement capabilities to ensure compliance.

Lastly, while respondents were overwhelmingly in favour of establishing a FITR, many emphasised that it is only one tool of many to counter foreign interference. Stakeholders urged the Government of Canada (GoC) to undertake structural and cultural reform and other legislative amendments within the national security apparatus, continue its outreach program with communities at risk from foreign interference, and to allocate additional resources towards the enforcement of existing counter-foreign interference legislation.

Context and Approach

Foreign interference (FI) poses a significant threat to Canada's democracy and national security. FI is activity undertaken by foreign states, or their proxies, to advance their own strategic objectives to the detriment of Canada's national interests. Such activity is deceptive, coercive, threatening and/or illegal. Malign foreign influence is a subset of FI and includes a covert or non-transparent undertakings at the direction of, or in association with a foreign principal, with the objective of exerting influence and affecting specific outcomes. FI, and malign foreign influence more specifically, is distinct from established, legal and legitimate channels of engagement through such activities as lobbying, advocacy efforts, and regular diplomatic activity.

On March 10, 2023, PS launched public and stakeholder consultations to guide the creation of a FITR in Canada, intended to increase transparency and general public awareness of foreign influence activities in Canada. Similar registries have been implemented in both the United States and Australia, and it is anticipated that a transparency scheme will come into force in the United Kingdom in 2024.

The consultations solicited feedback from the Canadian public and stakeholders on how Canada should design a FITR. Additionally, during the consultation period, public commentators made their views known in Canadian media. The Government of Canada welcomed all contributions and perspectives to help inform the development of FITR.

Online public consultations ran for sixty (60) days to solicit views from the Canadian public. Submissions could be made via an online survey or generic email inbox. Participation was voluntary and open to any member of the Canadian public. The survey asked six (6) open-ended questions pertaining to the FITR (see Annex A - Table 1). Respondents also had the opportunity to provide additional views in relation to the FITR and/or to upload supplementary documents as part of their response to the survey. In total, there were 932 survey responses, 71 separate email submissions, and 0 document uploads. These responses, which are discussed below, represent diverse views of the Canadian public.

The GoC also held stakeholder consultations with over 80 individual stakeholders, and over 40 different organizations, as well as individual academics and subject matter experts. These stakeholders represented business, community organizations, non-governmental organizations (NGOs), intelligence and security experts, academia, religious and community groups. Many of these stakeholders provided the GoC with detailed position papers, articulating their views on the establishment of a FITR.

While online consultations on the FITR closed on May 9, 2023, dialogue with stakeholders has remained ongoing, particularly with Provinces, Territories and National Indigenous Organizations.

What We Heard

Online responses

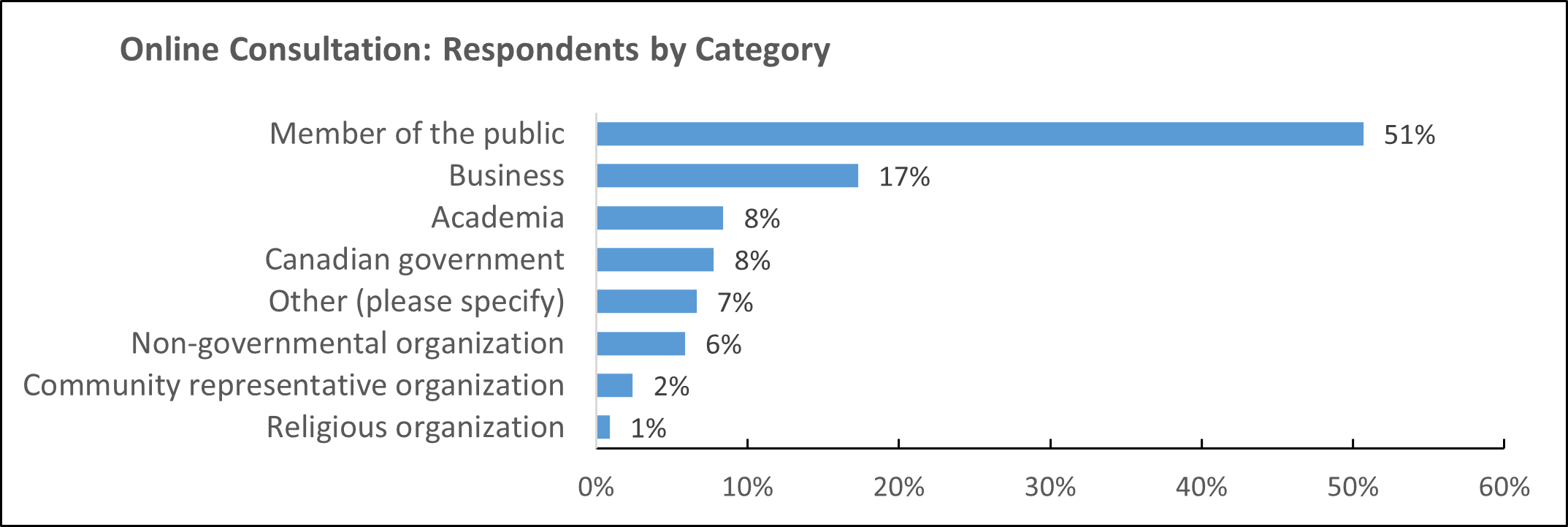

Between March 10 and May 9, 2023, 932 individuals provided responses to the online questionnaireFootnote 1. Respondents could identify themselves as belonging to one of seven (7) categories. As can be seen in Figure 1, a majority of respondents identified as “member of the public” (50%), with the next largest categories being business (18%) and academia (8%).

Figure 1: Respondents by category

Image description

A bar graph depicting the online respondents by category. 51% of respondents identified as members of the public, 17% as members of the business community, 8% as academics, 8% as members of the Canadian government, 6% as belonging to a non-governmental organization, 2% belonging to a community representative organization, 1% as a religious organization, while the remaining self-identified in the “other” category.

The questionnaire included six (6) questions. The first five (5) questions were preceded by prompts that proposed the possible definitions, exemptions, and/or penalties that the government GoC might use in a FITR. Respondents were then asked whether they agreed with these suggestions and if they had other suggestions they would like to make. The questions, and the number of responses to them using the online portal, are included in Annex A – Table 1.

PS analysed these responses using quantitative and qualitative methods. Quantitatively, a computer program read each response and scored the sentiment of each response. Scores were given on a scale of -1 to 1, where scores closer to 1 indicate positive emotions and scores close to -1 indicate negative emotions. Sentiment analysis indicates that overall response sentiment includes largely neutral language. This is included in Annex A – Table 2

A qualitative analysis shows that a majority of respondents support the registry. The respondents generally agreed with the definitions proposed in Questions 1 and 2. In Question 3, respondents disagreed strongly with the notion that there should be legitimate exemptions from registration activities. Most respondents answered Question 4 by noting that all registration information should be made public. In particular, many emphasised that any financial relationship be publicly disclosed. Virtually all respondents agreed with the premise of question 6. They believe that the GoC should enforce compliance through the use of scalable punishments, including both administrative monetary penalties (AMPs) and criminal penalties.

Stakeholder Consultations

Meetings with stakeholders were convened by the GoC and by non-governmental organizations. At each meeting, a GoC representative briefed stakeholders on the FITR and the possible considerations in its design and implementation. Stakeholders then engaged in roundtable discussions.

Stakeholder groups were broadly in favour of the introduction of a FITR, though many stressed that the registry would need to be properly designed, resourced, and enforced to be effective. As with the online consultations, stakeholders emphasised the FITR must be consistent with the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms. Unlike online consultations, stakeholders were virtually unanimous in their support of reasonable exemptions including legal advice and representation, diplomatic and consular activities by accredited officials, and situations where it is already transparent/clear that the individual or organisation is working on behalf of a foreign government.

Discussion of Key Themes

Definition of “Foreign Principal”

The consultation paper on FITR defined a foreign principal as “an entity that is owned or directed, in law or in practice, by a foreign government. This could, among others, include a foreign power, a foreign economic entity, a foreign political organization, or an individual or group with links to a foreign government.” Online respondents firmly agreed with this definition and that Canadians have a right to know about the depth of foreign influence, even legitimate forms of foreign influence, in Canada.

The online survey asked respondents if they believed other organizations or entities should be included as foreign principals. Many responses wrote that non-governmental entities and multinational corporations should also be included.

Stakeholders also agreed with the proposed definition, though they raised similar concerns. Some recommended that the GoC consider whether foreign owned/controlled media would need to register.

There was debate as to whether the registry should be country agnostic or country specific. One community representative argued that FI emanates from a few specific countries and, therefore, only these countries should be targeted. Some online respondents said that Canada's allies should be exempted from the registry. One academic contended that Canadian national interests are not always aligned with that of Canada's allies, thereby making it prudent to be aware of allied activity in Canada. However, the vast majority of stakeholders were in favour of country agnosticism based on the premise that transparency in public affairs is strongly supported. Further, a country-specific registry could unnecessarily stoke racial and ethnic exclusion, and result in a “blacklist”, rather than a means of transparency.

Scope of “Registrable Activity”

A FITR should shed light on activities that could influence public decision making in Canada. The consultation paper stated that such “activities might include parliamentary lobbying, general political lobbying and advocacy, disbursement, and communications activity.” When undertaken on behalf of a foreign principal, these activities could result in a registration obligation.

As the consultation paper noted, current laws in Canada may not adequately capture communications activity directed solely at members of the Canadian public (as opposed to public office holders/Canadian politicians). Stakeholder groups agreed that communications activity, as defined in the consultations paper, should be made registrable.

Some online respondents suggested that academics using foreign government grants should also be required to register. At a stakeholder meeting, one academic cautioned that a registry should not “inadvertently capture legitimate research… [as] we do not want to discourage research on important topics.”

Others emphasised the importance of simplicity. Some stakeholders felt that the exchange of money should constitute the threshold for a registrable activity. However, another speaker contended that some persons undertake influence activities for non-monetary reasons, such as seeking higher status within their government.

Arrangements to Influence Canada

In addition to these activities, the GoC also consulted on whether “arrangements” between foreign principals and those acting on their behalf should be registrable, where the intent of that arrangement is to undertake influence activities against Canadians. Respondents were asked to consider whether such arrangements should be explicit or implicit; if payment is required for an arrangement to be registrable; and whether the influence activity needs to already be underway for a registration requirement to be triggered.

One intelligence expert argued that arrangements should at least require the transfer of payment or advantage to the person acting on behalf of a foreign principal. A member of the public wrote that a loose definition of “arrangement” could put Canadians at risk for merely having unpopular opinions rather than for engaging in malign foreign influence.

Exemptions

Respondents and stakeholder were asked to consider whether there could be justifiable reasons to create exemptions from registration obligations. Conceivably, registration exemptions could include legal advice and representation, diplomatic and consular activities by accredited officials, and situations where it's already transparent/clear that the individual or organisation is working on behalf of a foreign government.

Stakeholder groups argued that the exemptions should, in principle, be as narrow as possible, so as to avoid creating loopholes. Likewise, a narrow exemption list would help the public and potential registrants view the FITR as an instrument of transparency, rather than a blacklist. This would serve the objective of encouraging potential registrants to register without fear of reprisal.

Online respondents were overwhelmingly against the provision of any exemption to registration. Of the minority of respondents who favoured exemptions, they also preferred a narrow list.

Legal practitioners argued for an exemption for persons who provide legal advice and representation to foreign governments on the grounds that any legal activity which relates to the Investment Canada Act and Competition Act already requires the same type of disclosure that the FITR would require.

Representatives of a consortium of universities argued that the GoC should establish an exemption for activities that are predominantly academic or scholastic in nature. They wish to see the exemption definition include teaching and research activities, including the communication of research findings by any means. Likewise, they wish to see a specific exemption for advocacy efforts on behalf of international students and temporary foreign workers.

A representative from a community organization argued that journalistic and academic activities should be exempt if the individual in question is acting in ways where their employer/funding organization is clearly identified as a foreign government or its proxy.

Finally, a member of the public wrote that “registration should only apply in the case of lobbying GoC officials and politicians, and not for private activities or general communications. It should not be based on the country of origin, ethnicity, business and civil society affiliations, and most importantly, on one's views.”

Information Disclosure

The consultations sought to gain feedback on the type of information registrants should be required to disclose, and whether this information should be made public. Online respondents were overwhelmingly in favour of public disclosure of all information. One stakeholder group, representing a community organization, wrote that registrants “should be required to adhere to information disclosure requirements similar to those set out in Section 5(2) of the Lobbying Act, and include disclosure of the relevant and necessary personal details that promote compliance and accountability.” Stakeholders also agreed that the FITR should require the specific details of the activities being undertaken.

Compliance

The overwhelming majority of online respondents agreed that there should be penalties for non-compliance, and that they should be scalable. Many respondents noted that monetary penalties alone may not deter wealthy individuals or entities. Some stakeholders agreed, noting that, for example, large corporate firms could withstand financial penalties more robustly than could small-medium enterprises, NGOs, universities, or individuals. This could call into question the impartiality of the FITR.

A community organization recommended that Canada establish a Commissioner of Foreign Influence, akin to the Commissioner of Lobbying. They recommend that this commissioner develop a code of conduct with specific reference to what is expected for diplomatic and consular personnel, including registration obligations.

There is also the challenge of investigation and enforcement. Many respondents noted that while the Canadian Security Intelligence Service (CSIS) is equipped to investigate FITR violations, it could face challenges in sharing its findings with law enforcement and prosecutorial agencies. Navigating the use of intelligence may remain a challenge in the implementation of a FITR. One ex-intelligence practitioner argued that Section 19 of the CSIS Act should be amended, so that intelligence could be shared more easily with law enforcement and other areas of society, including municipalities, academia, and businesses.

Building Trust

Many respondents emphasised that the success of the FITR depends on potential registrants' understanding of how to register, the implications of registration, and trust that the FITR will not impose an undue burden on legitimate principal-registrant relationships. According to some respondents, a complaint and redress mechanism could help address public concerns that the FITR could be used as a tool to unfairly target certain communities within Canada. Some community groups emphasised that FITR documents should be made available in languages other than English and French. They likewise recommend that the GoC officials administering the FITR undergo training before engaging with Canada's community groups.

Conclusion

Thank you to all who engaged with the GoC through the online and stakeholder consultation process. Your valuable input will help inform the development of a potential first-ever Foreign Influence Transparency Registry for Canada. The GoC sincerely appreciated the time and effort that went into providing feedback on this important initiative.

Annex A: Tables 1 & 2

Prompt |

Question |

Responses |

|

|---|---|---|---|

1 |

A foreign principal might include a foreign power, economic entity, political organization, or individual / group that is owned or directed, in law or in practice, by a foreign government. |

Do you agree that these types of organizations or entities should be included in the definition of “foreign principal”? In your view, are there others that should be included? |

861 |

2 |

Registrable activities might include parliamentary lobbying, general political lobbying and advocacy, disbursement, and communications activity. |

Do you agree that these activities should be registrable? Are there any other types of activities and/or arrangements that should be registrable? |

869 |

3 |

Registration exemptions could include legal advice and representation, diplomatic and consular activities by accredited officials, and situations where it's already transparent / clear that the individual or organisation is working on behalf of a foreign government. |

Do you agree that these activities should be exempt from registration obligations? What other activities (if any) should be exempt? |

850 |

4 |

Anybody who registers could be required to disclose personal details, such as activities undertaken, dates of the activities, and the nature of the relationship with the foreign principal. |

In your view, what kinds of information should registrants be required to disclose regarding their activities? To what extent should this information be made public? |

831 |

5 |

Compliance enforcement mechanisms could include administrative monetary penalties (AMPs), as well as criminal penalties. |

Do you agree that there should be penalties for non-compliance? If so, should these be scalable, including both AMPs and criminal penalties? |

867 |

6 |

(No prompt.) |

Do you have other views you wish to provide in relation to this consultation? |

758 |

Q1 |

Q2 |

Q3 |

Q4 |

Q5 |

Q6 |

Overall |

Values |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

0.09 |

0.11 |

-0.17 |

-0.12 |

-0.05 |

-0.29 |

-0.05 |

-1 = 100% negative 0 = neutral 1 = 100% positive |

The score of a document's sentiment indicates the overall emotion of a response, not whether or not the respondents support a registry.

- Date modified: